By Ilioné Schultz with Marie-Alix Détrie and Maria Varenikova. This article is part of a series on sexual violence in armed conflicts, commissioned and published by Zero Impunity.

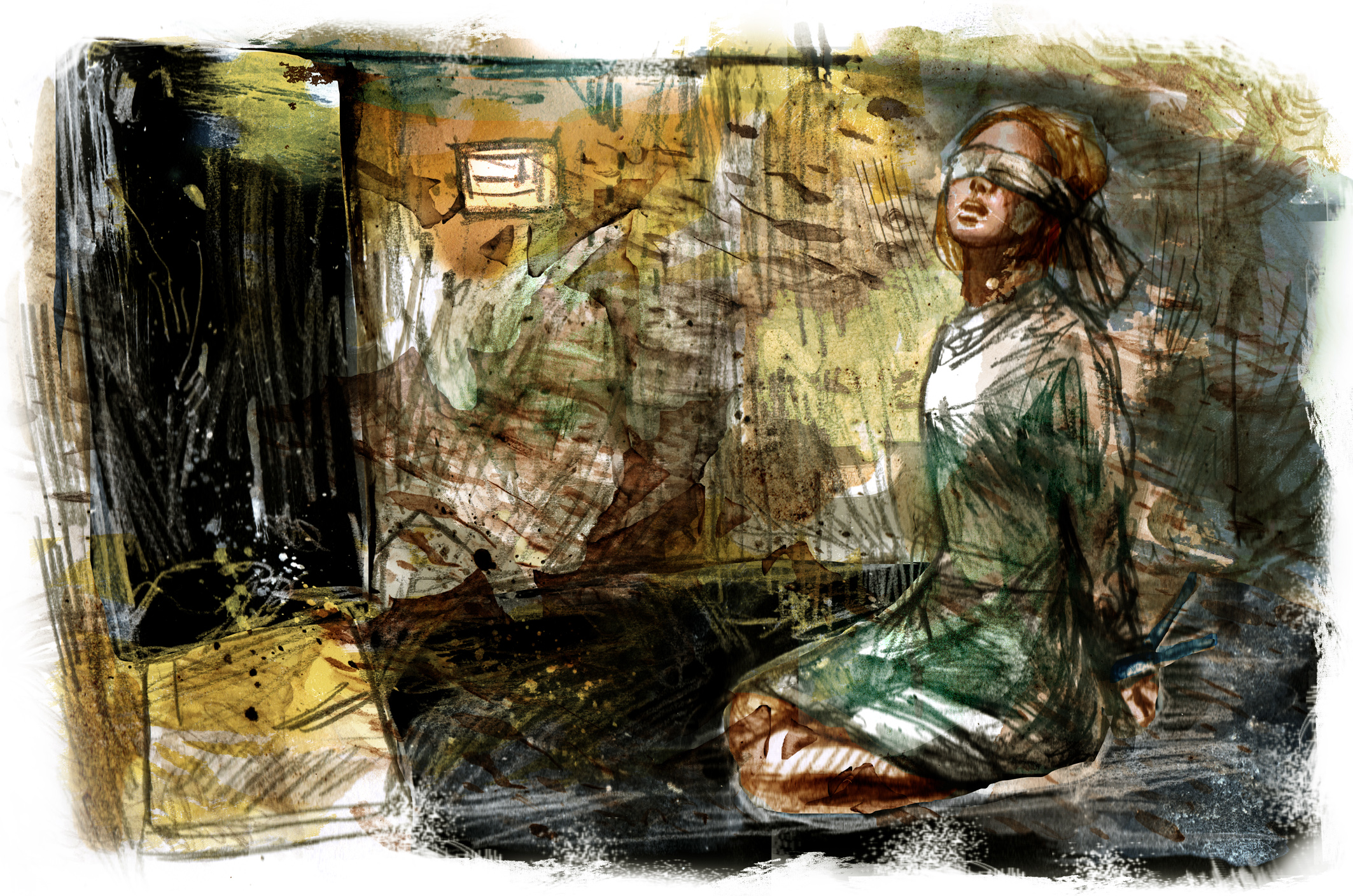

When [tooltip text=”Lena” gravity=”nw”]Name was changed.[/tooltip] wakes up, she can’t see anything. A blindfold is knotted over her eyes and her hands are bound behind her back. The 22-year-old woman doesn’t know where she is, but she can hear sounds and screams. She feels as if she might be in a basement. She’s thirsty. Panic rises in her throat until she begins to scream. A guard enters the room and starts beating her with a rifle until she stops. Then, he leaves.

By the next day, the young journalist still hasn’t been given any food or water. She starts to scream again and, once again, her guard hits her. Every once in a while, he grabs hold of her and gives her an injection. She starts sweating profusely and, soon, “loses all notion of time”. When she isn’t being harassed, Lena turns things over in her head. She knew that as a journalist, especially one from Kiev, it would be risky for her to travel to Donetsk, which is located in a Pro-Russian separatist region.

“If no one goes to Donetsk, then the world won’t know what is happening there,” she told herself at the time. However, she could never have imagined how her reporting trip in May 2014 would upend her life. Zero Impunity first spoke with Lena over Skype, after being connected with the young journalist through her lawyer, who also defends other former detainees. After her ordeal, Lena, who has light brown hair and eyes of the same hue, fled Ukraine and now lives in Germany.

Lena had never before disclosed the full details of what occurred during her detention– not to human rights activists, nor to the doctors who later treated her in Ukraine and then Germany.

However, on October 24, 2016, Lena– nervous, behind her computer screen– decided to share her story. After spending several days tied up in the basement, Lena was subjected to her first “interrogation” behind closed doors. The tension in the room reached new levels when her interrogators discovered photos in her camera showing the Euromaidan protests– a wave of opposition protests centred in Kiev’s Independence Square, which culminated in former President Viktor Yanukovych abandoning his presidency in early 2014.

As the interrogations continued, the guards transformed into torturers. They started hitting Lena’s head and stomach, not just with their fists but also with her camera. The message was clear: this is the price you pay for taking pictures. Even that wasn’t enough to make Lena talk– simply because she didn’t have much useful information to share. To push her to speak, they brought in another detainee. “If you don’t answer, he will pay!” During each interrogation– which lasted two or three hours– the blows would rain down on Lena.

Lena was more afraid of the possibility of rape than the relentless beatings that she was already receiving. The first few times they touched her, she was petrified. “When I was in my cell, the guards would touch my hair, stroke me,” she said. “Sometimes, they would make comments like ‘Come here, we’re going to play!’ Once, during an interrogation, one of the men opened my blouse. He put one hand on my cheek and another on my body. I was terrified.”

Almost two weeks had gone by when, one morning, Lena awoke without a blindfold. Several guards came in and brought her to a room that she had never seen before. There was a mattress in the middle of the floor and one of the superiors was reclining on it. The soldiers shoved her into the room. “Here, here’s a woman for your entertainment,” he said. Lena begged them not to touch her, but to no avail. Three or four of the soldiers started taking her clothes off. “Then, they started to rape me. First the men in black, the superiors. Then the men in green.”

On the other side of the screen, Lena stops speaking and swallows some water. Then, she takes a deep breath. When she starts speaking again, her voice sounds halting. “On that day, there were at least eight men,” she said. “I lost consciousness several times. They’d throw buckets of cold water over me to wake me up again.”

Lena thinks that the men in black were Russians or Chechens from their accents. Those in green were Ukrainians.

“They came in, then they’d leave again,” she said. “They’d blow marijuana smoke into my face to wake me up again. They were laughing and listening to music the whole time.” When they were finished with her, the rapists left Lena alone in the room. She lay still, half-naked, her battered body splayed out on the cold floor of the empty room. They brought her some food, which she didn’t eat, and some clothing, which she didn’t put on. When they brought her back to her room, the sun had gone down. Lena was released the next day.

Why did they wait until the very last day to rape her? Lena turned something that her interrogators had said over and over in her mind. “They told me that no one wanted to pay for my liberation: not my family, not the state,” she said. “I didn’t have anything of interest to them: no information and no money…” So did her jailers want to get their “money’s worth” out of her in another way? Did these separatist militiamen want to “break” her before releasing her to make sure that she would never come back, with her camera in hand, to witness and relate what was going on in the separatist areas?

Almost three years later, the once idealistic journalist is a shadow of her former self. She doesn’t know if she’ll ever get answers to these questions.

What happened to Lena is far from an isolated incident in the conflict that has gripped Ukraine for close to three years now. It appears as if the number of cases of sexual violence has risen sharply as the Ukrainian government remains locked in conflict with pro-Russian rebels in the eastern parts of the country. These rebels are supported by– or, in some cases, sent by– Moscow, though the Russian government hasn’t officially recognized a regular troop presence on the ground in Ukraine.

According to the report “Unspoken Pain,” published last February by the Justice for Peace in Donbas coalition, which is one of the rare organizations to have looked into the matter, about a third of those interviewed (including both civilians and detained soldiers) mentioned instances of sexual violence.“Even though the gravity of violence is appalling, it remains underreported and neglected by the authorities,” claim the authors of the report. These violations, which have been carried out against both men and women, mainly from spring 2014 to summer 2015, sometimes reach a degree of unimaginable violence. The authors of the report heard testimonies from two women whose breasts were punctured with a screwdriver and a man who was anally raped with a drill.

The sexual violence that has occurred in war-torn Ukraine ranges from threats to forced nudity to the electrocution of prisoners’ genitals to mutilations to rape.

According to the investigation carried out by Zero Impunity as well as the first reports published on the topic, these acts of violence most often occur in illegal detention centers, which range from former prisons to military or administrative buildings to requisitioned homes or factories to former schools or even basements.

The profiles of the victims vary immensely, as well. They range from combatants to outspoken members of the opposition to those simply suspected of harboring sympathies for the other side. Journalists have also been targeted as well as ethnic, religious or sexual minorities. Some of these prisoners are simply people who were at the wrong place at the wrong time. Very few female prisoners—and even fewer men—ever dare to testify what happened to them.

“It’s still too early for many of the victims who refuse to talk about the issue of sexual violence,” says Anna Mokrousova, a psychologist who works with the Blue Bird, an NGO that offers support to former prisoners. She has interviewed more than 300 former civilian detainees. Mokrousova is a former prisoner herself—and was threatened with rape while in detention. She says that Ukrainian society, which has been deeply marked by war, is not ready to hear their stories. “It’s hard for society to accept those who have been even more traumatized,” she says.

In this context, she continues, only the incidents used as instruments of propaganda get any attention, while real cases are scarcely considered. This is because the Ukrainian conflict plays out almost as much in the media as on the actual frontline.

To win hearts and minds, the media operations of the two opposing sides spread and embellish tales of their enemies using rape as a weapon of war.

Pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian websites often publish articles about their enemies carrying out sexual torture, mass rapes or raping minors. These stories are told in great detail, illustrated with fake and vulgar photos and filled with fake testimonies, which are sometimes produced by “victims” who were handed cash by the authors of the articles. This propaganda is largely distributed across social media and a huge role is played by an army of trolls working for Moscow, who sow hate while also discrediting the accounts of real victims. But the reality is sometimes just as dark as the tales sold by propagandists. While there seem to have been more rapes reported in the separatist territories, horrific acts of violence have also taken place on the other side of the frontline, in the areas controlled by forces from Kiev.

Zero Impunity met with Vadim* on October 7, 2016 in a dark corner of a deserted pub several hundred meters from the center of the Ukrainian capital. This veteran of a pro-Kiev battalion is thin, wiry and pale and he wears his head shaved. Vadim drinks his coffee with cream nervously. It wasn’t easy to organize this interview; Vadim is afraid of retaliation from members of his former battalion if they find out that he has talked. Yet almost three years later, he still hasn’t been able to recover from the scenes of violence that he was witness to.

Vadim, who was angered by the Russian annexation of Crimea, volunteered to fight for the cause in early summer 2014. After a short time in a unit that was “too violent”, he joined Aidar, a pro-Kiev volunteer battalion with a nefarious reputation. At the time, these volunteer units were playing a much larger role in the defence of Ukraine than the regular army, which was disorganised, undermanned, and corrupt. He began his service with Aidar in Shchastya, a town located several kilometers from the front. Vadim was assigned to guard duty on the base, which was a former police academy. His role was to keep the base’s makeshift prisons under surveillance. He immediately noticed disturbing behavior occurring within these buildings.

“When the soldiers came back from the front, they were in a state of shock and often very drunk,” Vadim remembered. “They’d go down into the basements [of the prison] to “let off steam” on the prisoners.” As Vadim worked shift after shift as a guard, he continued to witness acts of extreme violence, yet was powerless to stop it. He’d hear the sound of screams and the thud of blows from the other side of the door. But there is one scream that he’ll never forget.

One day, Vadim was the only guard assigned to a building where he had been told a female prisoner– suspected of being a separatist sniper because “she had been wearing a hood”– was being kept. (The myth of the ace female sniper resurfaces in many different conflicts in the former Soviet Union. Very often, women falsely accused of being snipers are raped in what is seen as payback for their alleged deeds.) One of the commanders entered the building. Vadim stops telling the story to clear his throat.

“A few minutes later, I heard the woman scream, ‘No, no! Don’t do it!’” he remembers. The sounds coming from the building left little doubt in his mind as to what was happening. “I was sure she was being raped,” Vadim says. He saw her the next day and noticed that she was “having difficulty walking”. Vadim has been eaten up with guilt for the past three years. He often thinks about what he could have done to stop what he heard. To redeem himself, he hopes that one day he’ll be able to testify before an international tribunal and reveal the key elements– names, dates and details– of what he witnessed.

This hoped-for tribunal should not just focus on crimes committed against those in detention. In the conflict zone in Ukraine, checkpoints are another place where unique pressures are put on women.

According to several interviews conducted by Zero Impunity, soldiers manning these spaces sometimes ask women to perform sexual favors in order to pass. In February 2017, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights published a report on sexual violence in Ukraine. It included the testimony of a local woman who had been gang raped after being stopped at a checkpoint run by members of the Vostok separatist battalion in Donetsk, the capital of the largest of the separatist republics. She was accused of having broken curfew.

“She was driven to what she thought was a police station that was occupied by the battalion,” the report reads.“During a three hour ordeal, she was beaten with an iron rod and raped by several men from the battalion.” They freed her the next day.

Not far from Donetsk lies the small town of Krasnohorivka. The town is in territory controlled by forces from Kiev, but it is only three kilometers from separatist lines. The scars of war are visible all across the town: windows are shattered, roofs destroyed and walls are pockmarked by the impact of bullets. The sound of artillery and shots being fired can be heard in the distance, and the area is teeming with soldiers.

One morning in mid-October 2016, we attended a small social event for local teenagers organized by local volunteers. As the young people listened to a small concert, Zero Impunity spoke with one of the volunteers, Elena Kosinova, who said in a hushed voice that many women in the village have been forced into prostitution for the soldiers. According to Kosinova, vulnerable women are most at risk of entering this trade, including “single mothers who have fallen on hard times” and “girls from ‘bad families’, who might not be even looking for money but just food.”

Kosinova does make a point to add that this prostitution fuelled by poverty takes place “without violence”. Near a village school in Krasnohorivka, Genia, age 16, stands, dragging on her cigarette. She wears a pink hood over her bleached hair and has already started using heavy make-up. Genia says she isn’t one of “the girls who go see the soldiers”. She claims that she “doesn’t want to get involved” with the soldiers or get tangled up in what she calls “fake love stories”– sexual encounters between the soldiers and local girls. Between two puffs, she admits that at least three of her friends “frequent” soldiers. Genia adds that she knows of “about twenty” other girls of her age who went to checkpoints to “meet” soldiers who Genia claims are constantly on the lookout for “underage girls”.

In a park in Kiev, we met Ilya Bogdanov– a former member of the FSB (the Russian secret services) who later switched sides and joined the Ukrainian ultranationalist paramilitary group Pravy Sektor. During the conversation, Bogdanov said he thought many of this poor behavior was likely tied to widespread alcoholism on the frontlines. Bogdanov may look like a towheaded teenager, but he doesn’t censor his words when he describes the zones where the conflict is taking place as “garbage”. According to Bogdanov, it’s a place where “13 or 14-year old girls drink with the soldiers” and “often end up screwing them, even though they are still children.” To Bogdanov’s knowledge, “the commanders said nothing about it.”

On the Ukrainian side, only 30% of police forces were still operational in the zones near the front in [tooltip text=”2016″ gravity=”nw”]From the 2016 report “In Search of Justice” published by the Center for Civic Liberties in Kiev.[/tooltip]. But even if there were working police units, it is unlikely that the young girls of Krasnohorivka– as well as most victims of sexual violence in Ukraine– would ever file a complaint.

The fear of retaliation and shame are just too strong. Even before the start of the recent conflict, survivors of rape were already discouraged from speaking out.

“Here, there is a strong culture of blaming victims: people tell you that it is your fault, that you shouldn’t have dressed in that way or drunk so much,” said Nastya Melnychenko, a Ukrainian activist in her thirties. Several years ago, Melnychenko survived sexual assault herself. In 2016, she launched a campaign on social media in Russia and Ukraine under the hashtag #imnotafraidtosayit as a way to open up discussion around this taboo topic.

Still, even Melnychenko feels little hope. “Here, the only way to avoid rape and sexual aggression is to not be born a woman,” she said. As for those who do summon up the courage to speak to the police, filing a complaint often turns into a nightmare. Police in Ukraine are sometimes perpetrators of sexual violence themselves. Moreover, the accused soldiers and officers often put pressure on the victims to withdraw their complaints.

After she was released, Lena, the Ukrainian journalist who was detained and abused in Donetsk, went directly to the police station in the separatist region to report what had been done to her. Nothing in the station inspired her confidence. Still, she “gathered all her strength” to describe what had happened to her, “except the rape”. A lieutenant listened with a contemptuous smile, before saying: “We can’t do anything for you.” When she asked to use a phone in the police station to call her friends and family, she was refused and shown the exit.

Lena’s fruitless and painful visit to the police took place in Donetsk in spring 2014. Since then, little has changed in this zone that is officially controlled by rebels– and, unofficially, by Moscow. The hope that victims of sexual violence might someday receive some kind of reparations is still just as faint.

In the separatist regions, the Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) and the Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR), Ukrainian structures and administration no longer function. Slowly, these structures have been replaced by a parallel justice system, which lacks sufficient personnel, is under-financed and opaque. For some activists, this chaos explains why, even if sexual violence has been committed on both sides of the frontline, it seems to be more widespread on the separatist side.

“The separatist territories are controlled by weapons and criminals while, in the parts of Ukraine under government control, there has still been a functional state and working prosecutors since the beginning of the conflict,” says Volodymyr Shcherbachenko, the coordinator of the report “Unspoken Pain.” “In the separatist territories, torture– including sexual violence– has been part of a policy put in place to intimidate the population.”

Zero Impunity requested access to Donetsk and Luhansk as part of this investigation. Both the governments of the DNR and LNR refused, without giving further explanation.

And what of the regions under Kiev’s control? There is less impunity in these zones but authorities still aren’t really in a position to offer survivors the real possibility of justice– especially in cases where the perpetrators happen to be part of the Ukrainian armed forces. That was the case for the man who raped 17-year-old Anna*.

Rain drummed down as we spoke to her in the shelter of a car parked below her student housing in an industrial suburb of Kiev. The young girl, who has long blond hair and a clear complexion, feels betrayed by the ruling of a judge in Ivankiv, a town in the region of Kiev. He sentenced her rapist to two years of probation and a fine of roughly 100 euros for anal rape.

Anal rape is not recognized as rape under Ukrainian law. The maximum sentence according to the Ukrainian penal code is three to seven years in prison, as compared to seven to 12 years for raping a minor. The man who assaulted Anna was a soldier who was part of a border protection unit. He had taken part in combat in the east of the country, however, at the time of the incident, he was stationed in Mlachivka, the village where Anna grew up, which is about a hundred kilometers north of Kiev.

The verdict against the man who assaulted Anna– which is dated June 10, 2016– includes a list of mitigating factors, including his “participation in anti-terrorist operations in the East” (the name used by Kiev to designate the conflict in the eastern part of the country). This ruling seems to show that authorities in Kiev are willing to pardon the domestic crimes of those it considers to be heroes in an all-important national struggle.

“The nationalist spirit is very strong [in Ukraine],” says Simon Papuashvili, the coordinator of the NGO International Partnership for Human Rights. “In situations like this where a country is attacked by a neighbor, those who defend the homeland are seen as heros.” Still, the public prosecutor appealed Anna’s case. The last ruling maintained the two-year probation while increasing the fine to 3,500 euros.

Anna’s family initially hoped to contest the ruling. “We are exhausted, my daughter can’t take any more of this legal process,” Anna’s mother told us in early March. On October 12, 2016, Zero Impunity contacted the judge who had made this controversial ruling, but he refused to comment on his decision.

The authorities in Kiev seem no more determined to bring to justice those responsible for crimes in conflict zones, despite the fact that they adopted a national plan of action in February 2016 to improve the protection of women in times of conflict.

The statistics provided in November 2016 by the office of the general prosecutor speak for themselves– there have only been seven investigations into sexual violence related to the Ukrainian conflict.

Three of those were closed from lack of evidence. For its part, the coalition “Justice for Peace in Donbas” has made a list of more than 200 victims. When asked, the office of the general prosecutor confirmed that a new preliminary investigation against a soldier who is suspected of committing rape was launched on February 7, 2017. Is it possible that the Ukrainian authorities just don’t see any advantage in carrying out further investigations ? The testimony of a former detainee who spent time in jails run by the SBU (the Ukrainian intelligence service) seems to imply that even Ukraine’s own secret services are implicated.

The recent UN report highlighted that acts of sexual violence were “most often perpetrated against individuals, especially men, who were detained by the Ukrainian secret services (SBU) and volunteer battalions.” On the other side of the frontlines, secret services– especially the Russians’– are also involved, according to a man who was formerly detained by the separatists and who mentioned the presence of “members of the FSB” amongst the command in this place where “sexual violence took place” and where “they exploited prostitutes”.

In this judicial desert, there’s just one glimmer of hope on the horizon: that of international justice. This is the hope that Alisa clings to. This young documentary filmmaker was raped in Kramatorsk three years ago by a man who said he was a former Russian officer. Zero Impunity met with Alisa in her Kiev apartment on October 9, 2016. In a show of rare courage in Ukraine today, Alisa wants everyone to know what happened to her. She hopes one day to bring her case to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). “If I do manage to do it, it won’t be about getting personal revenge,” she says. “It is more about all of the other girls like me.”

Out of the 3,000 cases involving violation of human rights in Ukraine that are currently in progress at the ECHR, none involve sexual violence. Alisa’s case would, in theory, be the first.

While the ECHR does not have the power to arrest those found guilty, victims can receive compensation. The International Criminal Court is the only court that can sentence war criminals when they can’t be tried in their own country. For Alisa, a large-scale international trial is “the only recourse”. The state of justice in Ukraine and the fact that it is impossible for authorities from Kiev to access the rebel territories leaves no doubt that the only route to justice will have to involve international actors. However, it remains to be seen if it is an effective solution. Even if Ukraine has not yet ratified the Rome Statute (the treaty that established the ICC), the ICC still has the ability to investigate crimes in all of Ukraine (including the separatist areas), no matter which nationalities are being investigated: Ukrainians, Russians, etc.

With this in mind, several activists have been collecting the testimonies of victims of sexual violence and have started to transfer them to the ICC. In an email dated March 9, the ICC said that, at this time, they “have not made any factual determination with regard to the alleged conduct”. The possibility of actually going to trial is very unlikely, all the more so because the waiting period is extremely long. On average, it takes a minimum of ten years to reach a trial.

“It’s going take a long time, a decade or maybe two. But if all goes well, in principle we could have an arrest warrant for [Russian president] Vladimir Putin for war crimes and crimes against humanity,” said Papuashvili, the coordinator of the NGO International Partnership for Human Rights. Papuashvili has already helped bring 300 cases involving non-sexual torture during conflict to the attention of the ICC and is currently working on another 400.

“The problem remains, however, that Russia, as a non-state party is not obliged to cooperate with the ICC and, so, in cases where Russian citizens are subject of the ICC arrest warrants, Russia will likely refuse surrendering its citizens to this court,” Papuashvili continued. “In such a case, the court has no right to intervene.”

For Olexandr Pavlichenko, one of the co-authors of the report “Unspoken Pain,” Russia is already working on clearing out the ranks of the separatists.

More and more separatist chiefs have been disappearing in “mysterious assassinations”, which Pavlichenko thinks are “scarcely disguised Russian moves to cleanse living memory.” He fears that, in the next two years, all of the criminals will have disappeared and, “with them, any chance at obtaining the truth”.

Alisa isn’t discouraged. She has decided to act. To break the silence around this violence, she has created a theatrical performance, which she has performed twice in Ukraine and once in Berlin. In the piece, she reenacts her own detention, including the rape. She goes so far as to take off all of her clothes on stage. The experience was intense… and not just for her. “Some of the audience members cry. Eventually, the violence of our war becomes little more than numbers. But in the theatre, you feel it live.”

To follow up and take action: become part of the Zero Impunity movement.

[box type=”info” ]Anna’s file is not the only one to end up in the hands of Ukrainian judges. The case against the Tornado battalion is one of the most high-profile affairs in modern Ukraine. About a third of the members of the battalion already had a criminal record when it was first formed in spring 2014. It has recently been disbanded and 12 of its members are currently being prosecuted for several crimes committed in the East including gang activity, torture and sexual violence. The military prosecutor in the case has chosen to center his communications strategy around these charges of sexual violence and clearly seems to want to make an example of this case. However, the task is far from easy. Very often, protestors disrupt hearings involving battalions in order to put pressure on the judges. The case against the Tornado battalion was no exception. According to the Attorney General, the accused men are responsible for assaulting more than 10 civilians. In at least two cases, the victims were raped. In one horrific incident, two people detained by the paramilitary group were allegedly “forced to rape another detainee who had been tied naked to a pommel horse,” stated military prosecutor Anatolii Matios on live television in June 2015. This summer, a court near Luhansk sentenced a member of the same battalion to six years in prison for rape– an occurrence exceptional enough to stand out. Could this be the beginning of a sincere willingness to bring justice to victims of sexual violence? “There is no real proof of torture and even less of sexual violence,” says the Tornado battalion’s main lawyer, Vladimir Yakimov. For Yakimov, those accusations are just a excuse for the trial to take place behind closed doors, in utmost secrecy. And yet, despite the closed door nature of the trial, the prosecution actually uploaded videos featuring reconstructions of the crimes as well as excerpts from the hearings, including those referencing sexual violence. The lawyer for the defense says this “fake trial” was organised because members of this battalion were interfering with contraband from separatist territories. For the lawyers and activists who have followed this case closely, there is little doubt of the extreme violence of this battalion– which seems to have sown terror in the village that it used as a base. On the other hand, the intentions of the government remain in the shadows. It is hard to know if this trial is really meant to condemn the criminals for their crimes or if it is a way to get rid of a battalion that had become too much trouble for the authorities. [/box]